|

Article 1 of 6 on Studying the Moon Pick a Crater and Take Note Michael Packer Comments: m·DOT·packer·AT·Yahoo·DOT·com |

|

NGC Moon! It’s entire surface of impact structure is

an outstanding catalogue of the kinematic morphology that still takes place in

our solar system. And it is by far the Arc de Triomphe of all monuments to

tribute man and woman who, in this case, were the principle observers of the

moon, scientists, philosophers and even off-springs of Greek theology. You got

to love that.

Indeed, pick a crater in your scope’s view, look up the name, and I guarantee the story behind the name will circle back to you and your unique relation to this hobby - at least as well as any

fortune cookie.

That’s certainly part of my observing plan.

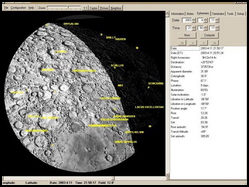

I’m in the backyard with either Antonín Rükl’s Atlas of the Moon, or my

portable running the free software VLA “Virtual Moon Atlas”. Both tools give a

brief description the feature was named after. I also have Wi-Fi,

so I can wiki the history in the driveway at the eyepiece.

Above, image links to Rükl’s Atlas, VLA Software, and Chuck Wood's Book (see below).

Link to Rükl’s Atlas on the-moon.wiki.

But of course, learning the object’s name is only

the cookie, not the fortune.

The fact that the moon, as an object, is bright

enough to see through a city's light dome (like San José) is undoubtedly a reason to study it further. Another

reason might be to take more than a cursory look at Rükl’s atlas and discover

that there are objects like shield volcanoes, fields of them, on

the lunar surface. Rükl’s introduction nicely depicts the range of features

you’ll want to look for. And in the back of the book there is a list of “50

Views of the Moon”. Along with reference photographs (nice to have at the

scope) this Messier-like inventory represents some of the finest examples of

moon geology. Somewhere down the line you will also want to get The Modern

Moon: A Personal View by Charles (Chuck) Wood. It is one of the few books that

neatly explains lunar impact structure and compares it with surrounding

features. He also runs the website LPOD, “Lunar Photo of the Day”, great

image resource, and the site lists his “Lunar 100” favorites.

Study the Moon: In these articles I promote the

concept of studying the moon verses observing it. I say study the moon for the

simple reason that most features benefit from the interplay of light and shadow

with the changing phase of the moon. In microscopy, microscopes are made to

produce both Bright Field (direct light) and Dark Field (oblique light) to

study very different detail from the same specimen. On the moon, we’re lucky to

have these two lighting techniques built in. Tycho benefits from this interplay

with its central mountains best seen under oblique light, 1 day after first or

last quarter, while its rays are better seen under direct light around full moon. See this LPOD for an excellent example of this interplay of light.

Continuing with the “study the moon” theme, I

suggest taking notes or sketches indicating time and date, lunar day, and more importantly the solar inclination (latitude) and colongitude. These values, particularly colongitude, I will use throughout these articles to nail down the position of the terminator. This pretty much requires you to download Virtual Moon Atlas and I’m

sure you’ll have it by the time you read Article 2 of 6. Anyway, as you explore the moon and find a phase that illuminates a feature well, its invaluable to note these angles so

you can share the experience or image it later.

Rupes Altai [Stephen Sharpley]

Seeing this object under the right

light was the fortune in the cookie. The mountain range made my subsequent view

of the popular lunar object Rupes Recta, Straight Wall, look like a protruding rim of a sidewalk one might trip over. Look for the crater chain(s) on the floor at the base of the scarp. This crater chain is ejecta from a younger impact perhaps located in the northwest.

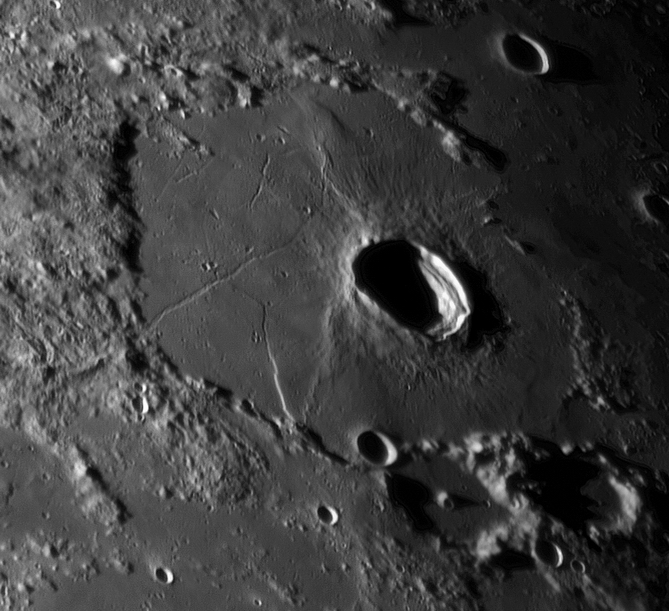

Outstanding features at colongitude of 147.2º also include crater Theophilus northward along the T and Lacus Mortis. Lacus Mortis is a nice Harry Potter name meaning Lake of Death. Anytime this lake is close to the T it deserves study and is probably in fact how it got its name. Around 147.2º, you’ll see the entire 104 km crater similar to the image below taken by Wes Higgins. Notice how the southern most fault appears to turn into a sunken lava tube at its northern end?! Very strange and some speculation has gone into explaining the stresses that formed this rille. If you look at the lake a month later around 151º half the crater is then surrounded by shadows from its own mountains west and the dark terminator to the east. The basaltic lava bed inside will look murky and much darker than the Lake of Dreams just south. And close to the T, the network of rilles will appear as scares in eerie relief. Really wicked!

104 km Lacus Mortis with 41 km Bürg inside [Wes Higgins]

As noted, you can observe Rupes Altai (also Theophilus and Lacus Mortis) at colongitude 147.2º around lunar day 19. See table below. While I certainly would not discount other observing times, this phase of the moon nicely positions the Nectarian scarp next to the terminator allowing the entire fault to be seen under near ideal oblique lighting.

The next article is titled “Observing Along the

T” where you will get a more systematic approach to studying the moon. But in

the mean time, why not pick out a crater and find the fortune behind the name.

Great Dates to Observe Rupes Altai

|

Librations and Moon/Sun positions for observer at 121.944°W 37.257°N 200 m

+ = Latitude of sub-solar point within 1.55° of target (= 0.000°) % = Moon above horizon/Sun below horizon for San Jose California

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table courtesy of Lunar Terminator Visualization Tool