|

Article 5 of 6 on Studying the Moon Good-Good, Good Librations Michael Packer Comments: m·DOT·packer·AT·Yahoo·DOT·com |

Whether we observe a full moon or a crescent moon

with earthshine we can only see 50% of the moon’s surface at one time. However

three principle (one might say good) orbital motions of the moon and earth

allow observers to glimpse about 59% of the Moon's surface over time. In other

words these motions, called librations, allow us to see surface detail on the

far side of the moon. Such features include the eastern mountain crests or

concentric ripples of the Eastern Impact Basin (Orientale), and views of polar

craters we now know contain water ice.

1) Longitudinal Libration:

The synchronous rotation that keeps the same face of the moon turned toward the

earth is only true on average because the moon's orbit in not circular but

eccentric. Hence the moon's rotation sometimes leads and sometimes lags its

orbital position. When the moon is at its perigee, its rotation is slower than

its orbital motion, and this allows us to see up to 8º of longitude of its

eastern (right) far side. Conversely, when the moon reaches its apogee, its

rotation is faster than its orbital motion and this reveals 8º of longitude of

its western (left) far side.

2) Libration in latitude is

a consequence of the moon's axis of rotation being slightly inclined to the

normal to the plane of its orbit around earth. This tilt (about 6.5°) allows an

observer to see a little more of the north polar region, and half a month

later, see a little more of the southern polar region.

3) Diurnal libration: An

observer at the equator who observes the moon throughout the night moves

laterally by one earth diameter. This gives rise to a diurnal libration, which

allows the person to view about an additional 1° worth of lunar longitude.

Similarly, observers sharing data at both poles of the earth would be able to

see about 1° of libration in latitude.

Eking out the extra 9%

surface edge detail from the above effects is not easy. For some limb objects

like Orientale, the planetary equivalent might be trying to positively identify

clouds at the edge of Mars. Be careful of fooling yourself into believing your

seeing something your not. Nevertheless, beginner lunar observers who check out

limb detail on consecutive nights and at their favorite phases quickly discover

these librations and readily appreciate them. After all, one of the best

rewards of amateur astronomy is discovery at the eyepiece. Excellent objects to

watch on consecutive nights are Mare Humboldtianum (found at “1 o’clock” on the

edge of the Moon’s disc) and Mare Marginis with Mare Smythii (2:30-3:00 o’clock

on edge of the Moon’s disc). The latter are southeast of Mare Crisium.

In VLA (Virtual Moon Atlas), one

can see the point of maximum libration for a given night by checking the box

found in the Display tab of the Configuration menu. Doing this displays a red

arrow at some point around the moon. Then, as one clicks forward the hour

“>” or day “>>” buttons under the Ephemeris tab, one can see this

libration pointer move around the moon and change in size to indicate the

location and magnitude of libration. Try this for the limb objects just

described and you’ll see when the good times are to watch them. If you discover a libration you like, keep an eye out for the anitpode libration to show up on the diametric opposite side a half month later or earlier. This is a particularly a good observing plan for the poles. Look for the times the north pole craters are visible and a half a month later south pole

craters like Cabeus should be observable.

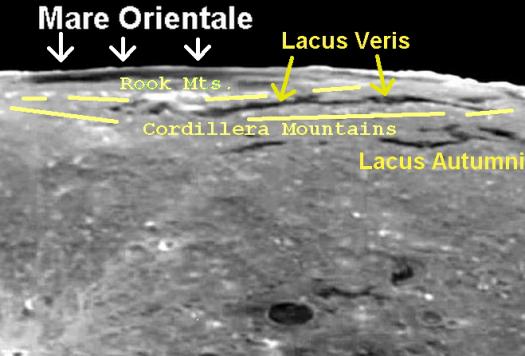

Located at the antipode of Mare Marginis is Mare Orientale at the center of Orientale Basin. Mare Orientale is an

elongated patch of dark mare material on the extreme western edge of the Moon.

Nearby are two other elongated patches of dark material, Autumni and Veris, and

two mountain ranges Cordillera and Rook.

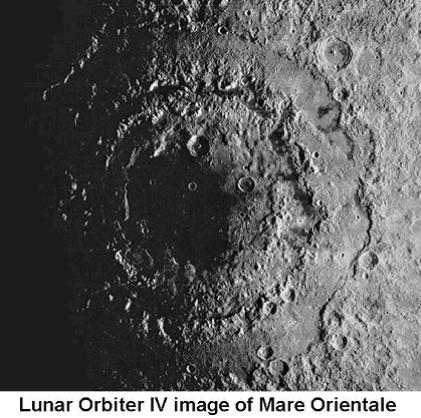

The Lunar Orbiter image

shows what William K. Hartmann projected in the 1960’s: That Oriantale is in

fact a large and relatively fresh impact basin. It’s surface ripples well

preserved or frozen as concentric mountain rings around a central sea of lava.

The diameter of this basin out to the Cordillera Mountains is 930 kilometers.

The impact is believed to be post Imbrian (about 3.2 billion years ago) making

it likely the youngest basin on the moon.

The best time to view the

basin is before sunrise (or night before) as indicated in the table below.

Libration in longitude close to -8º are in theory best for viewing the most of

Orientale but one needs to account for observing while it is still dark and at

best sun angles and these times will not necessarily fall at maximum libration.

High sun angle around full moon gives the best contrast of the mare regions

against the surrounding highlands while grazing sun angles (and here you want

to observe right before sunrise) give the best relief of the highland mountains

Cordillera and Rook. So take the time to look over nights and set your alarm

clock for the mornings. Good observing and I will be out there with you.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||